The Language of Museums

By Sarah Franke, Principal, MuseumBabel

Our modern definition of the museum is clear - museums are not just warehouses for stuff. They are fundamentally social institutions. And there is nothing more social than language. It’s the building block of human relationships and our primary channel of learning and exchange.

Recent research indicates that more than one in five US residents (over 21%) speak a language other than English at home. Over 300 languages are spoken throughout the United States. That’s not counting the languages spoken by tourists and visitors coming to the US from all over the world. Museums are reacting to these demographic transformations in various ways. How do they fit into this multilingual picture?

In cooperation with the New England Museum Association, I distributed a survey in April 2015 to find out what today's multilingual museum landscape looks like. We received 72 responses from museums in New England. Of these respondents, 47% report offering multilingual resources and 53% say they do not offer any at this time.

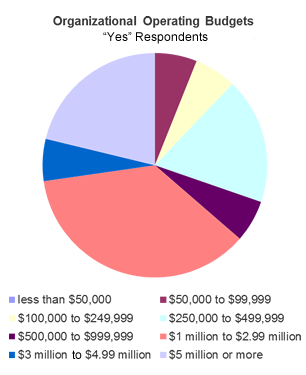

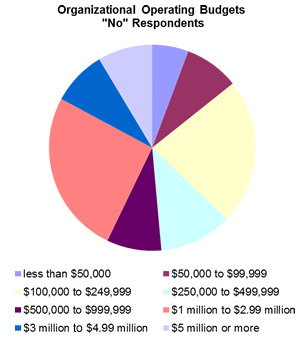

Of those museums that do offer multilingual resources, they are located overwhelmingly in urban areas (74%). Slightly less than one third (29.4%) have operating budgets under $500,000. The largest segment of “yes” respondents fall within the $1 and $3 million (35%) budget range; the remaining “yes” museums have budgets greater than $3 million (27%). While the “no” respondents are fairly evenly distributed across budget size and geography, the “yes” respondents trend toward larger institutions in and near cities.

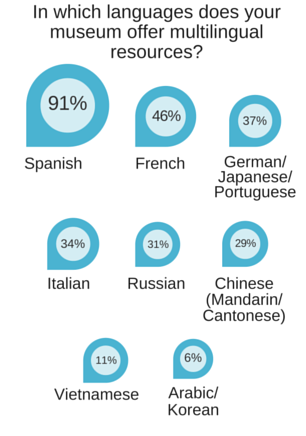

The vast majority of multilingual resources are in Spanish. In second place is French, followed by German, Japanese, and Portuguese. In a nod to New England’s ever increasing cultural and linguistic diversity, museums also offer materials in Korean, Arabic, Polish, and Khmer, among other languages.

Several respondents said that based on visitor feedback and demographic data, there was no need to offer resources in another language. For example, one respondent wrote: “Being in a very rural area, we don't get many non-English speaking visitors to the museum or to the region. [It] is not known for its diversity and the town we live in…is even less diverse. So this is not a high priority for us right now.” It’s understandable that for some organizations, developing multilingual materials isn’t a smart, strategic, or mission-appropriate activity.

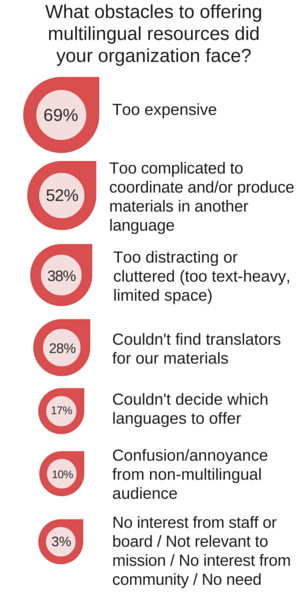

The vast majority of “no” respondents cited time and financial shortages as the primary obstacle to creating these materials - a familiar sentiment for those of us in the field! This resource scarcity presents a substantial challenge, despite eagerness to begin these types of projects. “It is one of the things on our 'to-do' list, but it never seems to be a top priority in terms of resources (both financial and in staff time)," said one museum professional in the survey.

That said, the museums that do offer multilingual resources feel strongly that the effort to develop and share them is worth it. These reasons are reinforced by current research. Multilingualism is an important, forward-looking aspect of museum sustainability. We need only glance at the demographic data to see where things stand. Although 38% of US residents are ethnic minorities, people who identify as minorities make up only nine percent of frequent museum visitors.[1] There’s huge potential for museums to better serve the people around them and simultaneously grow their audiences.

Engagement of multilingual groups, which often overlap with minority groups, is vital to the long-term health of our field. Chief Market Engagement Officer for IMPACTS Research and Development and nonprofit trends blogger Colleen Dilenschneider recently released very compelling data showing how quickly museums need to respond to demographic trends if they want to maintain or grow their visitation.[2] As existing audiences, who are typically white, older, and well-off, shrink, they are not being replaced at sustainable rates by other visitors. Meanwhile, second- and third-generation immigrants are driving population growth. Dilenschneider cites increased acculturation (adopting mainstream trends, like visits to museums) from first to second to third generations as the key. Multilingual offerings reach new audiences, giving museums an edge to attract and retain the next generation of visitors and their families.

A crucial point is when museums cultivate these relationships with their visitors. The data identifies the year 2020 as the tipping point. Like someone choosing a favorite brand of toothpaste, these affinities and preferences are established at a young age. Museums who start building connections with emerging audiences through outreach and targeted programs now will reap the benefits in five years. These organizations are relevant, accessible, and appealing to an entirely new segment of the market.

The data from this survey supports these findings. Most “yes” respondents – an impressive 97% - said the purpose of offering multilingual resources is to increase accessibility. Nearly 80% stated they offer these resources to attract and accommodate local audiences. Importantly, multilingual resources help museums fulfill our missions as public institutions and respond to the needs of both our current and potential visitors. When we consider factors like language use within the museum space, if the exhibition content is culturally inclusive, and who someone may visit the museum with, we begin to understand how the museum fits into someone’s life in a larger context.[3],[4]

What does this look like in practice? According to the survey, multilingual staff members are the most common asset in the museum, tied with printed gallery or exhibition guides. Continuing the trend of printed resources, interpretive panels and marketing materials are the next most common items on offer. Understandably, the depth of multilingualism in the museum also varies; in an example from the survey, one museum noted that while some of their main wall texts are bilingual (English-Spanish), other collateral is available in additional languages. About one-third of “yes” survey respondents present their visitors with educational activities and wayfinding/signage – a basic but particularly important consideration for multilingual groups navigating and interacting with the museum.

When done with intention, the results of this work are numerous and significant. Benefits to both the museum and the visitor include improved opportunities for self-directed and intergenerational learning, plus happy visitors who feel welcome and appreciated. One survey respondent wrote about both the practical and empathetic aspects of multilingualism in the museum: “Multilingual brochures or interpretive materials are really not that difficult or expensive to create! You may have excellent resources within your own community of members, donors, neighbors and other stakeholder[s] who can create translations or fund professional ones. If you have ever travelled in a foreign country where you do not speak the language, you will agree that ANY resources in your language [are] welcomed and even a small bit of information can improve your visit.”[5]

Multilingual museums enhance learning and accessibility. Almost all multilingual visitors or family groups use both English and their other language to interpret and make meaning from an exhibit.[6] The practice of code switching allows adults to facilitate the experience for their children, using the language and tone that’s most comfortable in that particular situation. In several studies, observers noted a higher rate of adults answering questions or pointing out interesting points to their kids while in multilingual-friendly exhibits.[7] When viewed through the lens of educational outcomes, visitors of all ages can better access and share information with one another. In a country where four million kids are ESL students, this level of comfort, ownership, and exchange throughout a museum visit is invaluable.

In addition to supporting informal and independent learning in the museum, incorporating multilingual materials also has profound emotional effects. Visitors whose languages are represented in the museum space consistently report higher rates of goodwill and positive attitudes toward that organization. Interestingly, English-only speakers also generally responded well to multilingual content, eliminating a major objection that other languages are distracting, inappropriate, or confusing.[8]

In fact, most people say their primary motivation for visiting a museum is to have a socially shared experience.[9] When that experience is facilitated in someone’s native language through labels, signage, or, best of all, multilingual staff, its impact is exponentially increased. To quote Nelson Mandela, “If you talk to a man in a language he understands, that goes to his head. If you talk to him in his language, that goes to his heart.”[10] Planting the seed of this relationship is an important societal function, essential for the happiness and wellbeing of our visitors.

In our survey, multilingual museums reported deep and meaningful benefits, particularly in how their role in their community is perceived. Nearly all noted these resources lead to the museum being seen as more welcoming and open. More than 75% of respondents said these resources have helped reinforce their public value or mission. Additionally, more than half of the multilingual museum cohort observed increased and more diverse visitation, as well as deeper visitor engagement with their institution. We already know the public is essential to the success and, indeed, the purpose of our field. These responses show how powerfully multilingualism propels museums toward being essential to the public, too.

Looking ahead to the coming years, museums cannot afford to ignore the role language plays, both for the health of the field and for the good of our neighbors. Let’s explicitly and intentionally recognize the diversity already present around so many of our institutions. Let’s be conscious of what message we send through our staff and leadership, our printed texts and digital presence. Let’s welcome multilingualism as a cultural asset, not dismiss it as a burden. Diversity is a fact. Inclusion is a choice.

Sarah presented the results of her survey at the 2015 NEMA Conference on Thursday, November 5 in a session entitled, "Speaking My Language: The Whys, and Hows of Multilingual Museums."

[1] Reach Advisors Analysis of Census and Survey Data, in “Demographic Transformation and the Future of Museums”, Center for the Future of Museums, an initiative of American Association of Museums (Washington, D.C.: The AAM Press, 2010), http://www.aam-us.org/docs/center-for-the-future-of-museums/demotransaam2010.pdf, 5.

[2] Dilenschneider, Colleen, “Visitation to Increase if Cultural Organizations Evolve Engagement Models (DATA)”, Know Your Own Bone (blog), April 22, 2015, http://colleendilen.com/2015/04/22/visitation-to-increase-if-cultural-organizations-evolve-engagement-models-data.

[3] Steve Yalowitz, Cecelia Garibay, Nan Renner, and Carlos Plaza, “Bilingual Exhibit Research Initiative: Institutional and Intergenerational Experiences with Bilingual Exhibitions”, National Science Foundation Grant DRL#1265662, September 2013, 15-16.

[4] Sofia Gutierrez and Briley Rasmussen, “Code-Switching in the Art Museum: Increasing Access for English Learners”, in Multiculturalism in Art Museums Today, eds. Joni Boyd Acuff and Laura Evans: (London: Roman & Littlefield, 2014), 149-150.

[5] See Graphic 10 “How did your museum produce its multilingual content?” for affirmation of this statement. Most museums that responded “yes” on the survey report using internal resources ranging from staff to board to volunteers to develop their multilingual resources.

[6] Yalowitz, “Bilingual Exhibit Research Initiative”, 6-7; 26-29.

[7] Sue Allen, Ph.D., “Secrets of Circles Summative Evaluation Report, Prepared for the Children’s Discovery Museum of San José”, Allen & Associates (San Mateo, CA, 2007), 11, 24.

[8] Ibid, 62-63.

[9] Marilyn G. Hood, “Staying Away: Why People Choose Not to Visit Museums.”, in Reinventing the Museum, ed. Gail Anderson (Lanham, MD: Altamira Press, 2004), 150-157.

[10] Mandela, Nelson. In “How you can learn Languages”, European Commission. (Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2010), 9.