Connecting the Climate Change Dots

By Raney Bench, Executive Director, Mount Desert Island Historical Society

Recently the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released a new report documenting the accelerating pace of human caused climate change and the impacts it is having on our environment. According to National Public Radio reporter Rebecca Hersher, the report is unique in two ways; first, it breaks down climate change predictions and impacts by region; and second, paleoclimate research was included in each chapter of the report.[1] The new aspects of the report are important for collecting organizations because they provide entry points where museums and archives can step into the conversation and support climate change research and education in their own communities. Our collections hold centuries of data about climate, often in unexpected sources. Through innovative partnerships, museums and archives can be important sources of information to scientists and local leaders, while interpreting climate findings for general audiences.

Finding the data

Three examples of how museum collections are informing and supporting climate research can shine some light on how more organizations can get involved. The Monterey Bay Aquarium recently launched the Ocean Memory Lab, where they are using historic collections to measure past environmental conditions found in the ocean, comparing those to conditions found today. One study uses Victorian seaweed pressings to measure nitrogen levels over the past 140 years. Chief Scientist Kyle Van Houtan points out that “Having only a few decades of data simply isn’t enough to answer questions (about what a ‘normal’ ocean looks like.)”

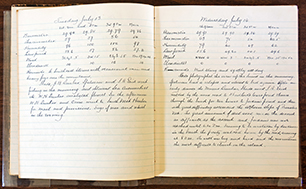

A second study is being conducted in England using historic tide records to measure the speed and scope of sea level rise. On Hilbre Island outside of Liverpool, residents in the 1800s kept detailed logbooks recording the height of tide every fifteen minutes. This information can be compared with modern tide observations to better understand and predict the impacts of sea level rise. Digitizing the logbooks and making them accessible to scientists has added over a century of data to review and compare, improving our understanding of how climate change is impacting the oceans. Lauren Sommer from NPR’s Short Wave notes that “scientists say a crucial way to make really detailed forecasts about the future is to find these long-running datasets from the past.”

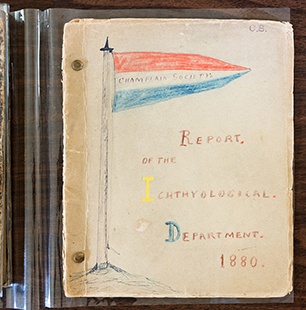

In the 1880s on Mount Desert Island, Maine, a group of students from Harvard recorded observations of the natural environment in a series of detailed logbooks and reports, which are being used to launch a new initiative to understand the impacts of climate change on the island. Called Landscape of Change, the goals of the initiative are to pull information from historic records to create a more complete picture of island ecosystems in the past, which is then used to measure change in real time. This information is shared with the public and community leaders to facilitate conversation and policy decisions about climate mitigation strategies and climate resilience planning.

Champlain Society Journal. Photo by Jennifer Booher.

Landscape of Change brings together diverse partners who had not previously worked together, but share the value of understanding and protecting Mount Desert Island’s human and natural histories. Led by the Mount Desert Island Historical Society, partners include Acadia National Park and their non-profit research partner the Schoodic Institute, the Mount Desert Island Biological Laboratory which relies on marine species in the Gulf of Maine to support research in human health, College of the Atlantic, and A Climate to Thrive, a non-profit committed to climate change advocacy and education. The project will replicate a study released in 2010 that compared a historic catalog of island plants published in 1894 with a modern inventory. The study found that 30% of the plant species found on the island in 1894 were missing from the landscape in 2010. This same level of categorical comparison needs to be replicated for birds, insects, marine invertebrates, inter-tidal zones, and more. Temperatures in the Gulf of Maine are rising faster than in any other part of the ocean world-wide, so there is a pressing need to document what was in the Gulf and what is there now, so scientists can measure what is disappearing and how quickly.

There is a long list of sources that can be identified for possible information. Logbooks from boats, farmers, timber companies, shipping records, and lighthouse keeper’s journals are all great sources of information, but there are gems found in letters and diaries, photographs and paintings too. Information about when local ponds first froze over in winter or ice out in the spring can tell scientists much about warming temperatures and trends in local climate; letters and diaries recording the first signs of spring and when certain species of birds arrived in the region can inform scientists about migration patterns. The opportunities are almost endless.

What to do with the data

Landscape of Change would not be possible if the original logbooks kept in the 1880s had not been transcribed and digitized by volunteers. Knowing what is in our collections is the first step in being able to share that information, and making it available to the public is part of our work as museums and archives. Once you know what’s in your collection, share it - reach out and let other non-profits, research, and education organizations know what you have and how they can access it.

Champlain Society Log Book. Photo by Jennifer Booher.

The second step is to form collaborative partnerships that bring together a diverse group of people with varied expertise to help advance the mission of each organization, while working more efficiently and effectively. The Mount Desert Island Historical Society is not in a position to study and publish climate research, but we do hold the collections that scientists need for that work, and we are expert at interpreting island history for the public. Scientists have ways of making their findings and recommendations public, but often the audience is limited. Museums and archives can be valued partners to climate change messaging because we have access to different audiences who may not otherwise be exposed to this information.

Keeping the story local helps. Most people have experienced some form of climate impact, from weather, to changes in bird, plant, and insect populations, to changes in the watershed; connecting what is happening to individuals where they live, work, and play with broader climate science can help break down barriers or misinformation. Public programs, exhibits, publications, and education outreach are all ways museums and archives interact with our community, and connecting collections and outreach with new strategic partners will expand audiences and impact.

Don’t be afraid to think outside of the box and challenge assumptions. Historic records usually don’t meet the exacting and precise standards modern scientists use as evidence; there weren’t GPS locations for specimens, measurements and measuring tools were not as precise as those available today, and natural history specimens may be categorized under new genus and species names. Landscape of Change science partners recognized these challenges and others, but stayed focused on the information that could be gathered, rather than what could not. With this flexible perspective on historic records, long datasets covering over a century of observations in one location still produced concrete findings on missing and invasive species, the speed and degree of sea level rise and temperature change, changing migration patterns, and threats to the boreal forests. We have just scratched the surface of the information available to us from historic collections.

Involving the Community

Historic records include tons of observations about the world. Volunteers and staff can help mine these records and pull out specific accounts, observations, and measurements. Transcribing historic records is also an important part of the process, and there are free on-line communities where museums and archives can post records and ask volunteers to transcribe all or parts of the documents.

Accessing and publicizing historic records is only one part of the process. Modern observations are necessary for comparison, which provides a great opportunity for community engagement. Landscape of Change relies on historic documents written between 1880-1920, which were recorded by students and interested citizens, not necessarily trained scientists. Schoodic Institute and the Historical Society are using this fact to inspire people to observe and record the world around them using apps like eBird and iNaturalist. We have invited people to walk the trails where the historic observations were recorded and make new recordings so we can know which species might be missing, if there are new species, and the health of the overall populations.

Climate change is a complex issue with many variables that are subject to change. By modeling the two new aspects of the Intergovernmental Panel report; including historic records in all aspects of climate research, and linking global trends to local conditions and solutions; museums can promote stronger climate change literacy, empower people to recognize how change is affecting their lives, and develop community solutions for mitigation and resiliency. Our collections will help connect the dots of climate change in our own backyards, and strengthen our community commitment to address these issues together.

[1] Paleoclimate researchers study past climate to understand how the earth will change in the future.

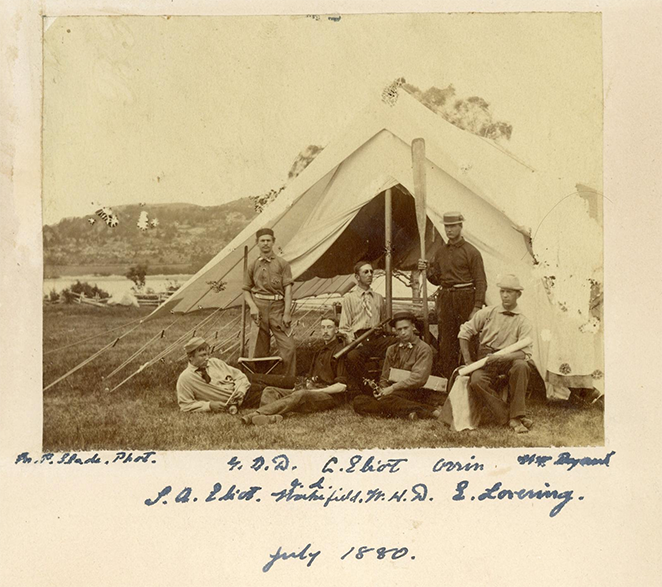

Header photo: Champlain Society, Camp Pemetic. Photo Mount Desert Island Historical Society