The Digital Frontline

By Kate Petterson and Katherine Burton Jones

The COVID-19 pandemic and related closures has had a profound impact on museums and museum staff over the past two years. Many institutions turned to digital programming to reach audiences unable to enter the physical museum space due to federal and state mandated closures. To better understand this ongoing digital transformation, we conducted two nationwide surveys, the first from May to June of 2021 and the second from August to September of 2021. The surveys sought to understand how digital transformation took place, the successes and pitfalls, who drove the digital change, and the outlook on the future of digital. Perhaps most significantly, the survey results also highlighted the importance of the educational staff in the institutions and the burden placed on them, often with too few resources and minimal staffing levels.

Background

In June of 2020, the American Alliance of Museums conducted a National Survey of COVID-19 Impact on United States Museums of 760 museums. AAM’s survey results highlighted that the majority of services provided during COVID closures or lockdowns were educational resources for children, parents, teachers (75%), college students and adults (54%), along with live or recorded video lectures (60%). In AAM’s survey 64% of participating institutions anticipated having to cut back on education, programming, and other public services due to budget shortfalls and/or staff reductions. The takeaway: educational opportunities and resources were incredibly important when the pandemic began, yet it was precisely in these areas that institutions anticipated making cuts. The October 2020 AAM survey showed that 40% of education staff were affected by layoffs or furloughs. Additionally, 67% of respondents reported having to cut back on education, programming or other public services due to budget shortfalls and/or staff reductions. In AAM’s March 2021 survey 48% of full and part-time museum employees reported an increased workload, highlighting the stress placed on employees due to the pandemic.

Our Surveys

Our national surveys, administered from May to June and August to September of 2021, sought to clarify digital transformation during this turbulent period. Survey 1 received eighty-seven complete responses and 59% of participating institutions were small to mid-sized (thirty or fewer full-time employees). Responses came mostly from art and history museums located in the Southeast (48%) and New England (20%). Respondents were also predominantly director (31%) and manager (51%) level museum employees. All but one institution offered virtual/digital programming during the initial lockdown. Fifty-eight percent of respondents monetized digital programming, but the majority charged only between $5-10 dollars (27%) or simply suggested a donation (22%). Only 15% charged over forty dollars for a program.

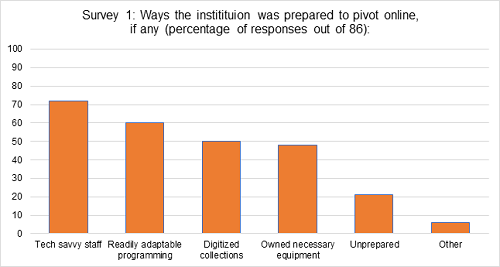

In Survey 1 we asked respondents who drove digital transformation at their institution and most responses indicated that it was driven both by staff members as well as the institution’s initial pivot plan (73%). Highlighting the important role that staff played in this rapid transformation, 72% of respondents stated that having tech savvy staff was one of the most important aspects of their ability to pivot online, followed by readily adaptable programming, digitized collections, and owning necessary equipment (Fig. 1). Only 21% of respondents stated they were completely unprepared for the quick shift to digital. Staff capability and drive clearly played an important role in the success of the quick digital transformation during 2020.

Figure 1

When asked in Survey 1 about sustainability issues for digital programming, 62% of responses raised concerns over staffing capacity and the time and resources it takes to make digital programs.

Survey 2 (August-September 2021) received seventy-four complete responses and once again history and art museums were the most common. Sixty-six percent of the institutions had thirty full-time employees or less and the geographic areas that responded the most were New England (31%) and the Mid-Atlantic (22%). Again, most respondents were predominantly at the director (30%) or manager level (45%). In this survey, 39% of respondents said they were still going strong with digital offerings, while 54% had reduced digital offerings, and 7% had ceased digital offerings altogether. Only about 37% of respondents to Survey 2 said that layoffs and furloughs absolutely affected them. When asked about the greatest hurdles respondents faced for programming to return to pre-pandemic levels, 46% stated health and safety concerns regarding COVID-19, 44% said decreased revenue, and 42% said reduced staff. The fact that reduced staff features prominently highlights the central role that adequate staffing plays in providing education and public programming.

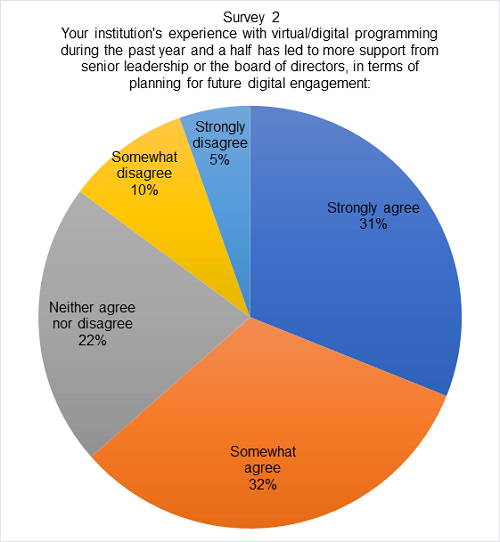

In Survey 2, we asked whether the institution’s experience with virtual/digital programming during the past year and a half had led to more support from senior leadership or the board of directors for future digital engagement. Thirty-one percent of respondents strongly agreed that they now have more support from senior leadership for future digital engagement, while 32% somewhat agreed with this statement (Fig. 2).

Figure 2

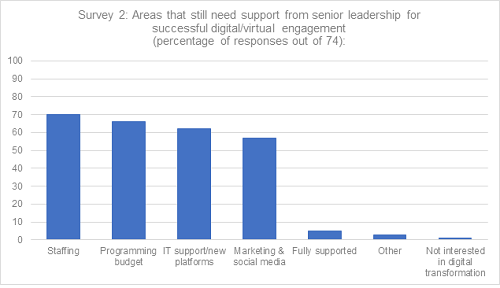

However, when asked what areas still needed support from senior leadership for successful digital/virtual engagement 70% of respondents said staffing, 66% said programming budget, 62% said IT support/new platforms, and 57% said marketing and social media required further support (Fig. 3). Only 5% of museums felt fully supported for future digital engagement, while only one museum said the institution was not interested in pursuing digital further.

Figure 3

Education and digital engagement, which kept museums connected to their local communities and a wider audience, appear to be the most vulnerable to budget cutbacks, as indicated by AAM’s June 2020 survey. And while many of the respondents to our surveys said they receive support from senior leadership for future digital engagement (Fig. 2), the need for more staffing, increased programming budget, and more marketing and social media support indicates that there are still issues in supporting digital engagement, especially for small to mid-sized museums.

Some of the open-ended responses we received in Survey 2 regarding staffing and education illustrate how hard museum educators work to reach their communities and how much strain the digital pivot with a lack of staffing and resources has been.

- “I have found that even though senior staff/BOT [board of trustees] are supportive of the efforts to create/offer virtual programming, they do not understand the time, money, and difficulty in making virtual programming. They think it is easy to live stream or convert a program to digital, but they don't understand all the extra effort and tech support that goes into it.”

- “These are jobs, not just extra tasks you can randomly drop on educators.”

- “Staffing is a big issue, buy in from other departments to share their work/information on a digital platform (filming behind the scenes segments), [and] the learning curve on creating quality content using Adobe/video editing software.”

- “We were expected to produce digital content without any training, clear guidance, or financial support for technology.”

- “We do make less money on virtual programs, as they are not priced as high as in-person programs so while we want to offer them for access reasons, they do not contribute as much to covering our education expenses.”

Some of these responses, in part, may explain why AAM’s March 2021 survey showed that 48% of full and part-time museum employees reported an increased workload as educational staff needed to learn new skills in order to provide digital programming.

Not all comments from survey respondents were complaints regarding difficulties due to digital transformation. Respondents also mentioned reaching audiences that were not part of the onsite, physical constituencies, including former members who had moved out of the area. One person noted: “We have reached schools that we never would have for geographic reasons in school programs, adult classes have offered flexibility to working and otherwise occupied adults, free programming created good will.” Another respondent stated that virtual was “[An] incredible opportunity to engage previously dis-engaged audiences, or audiences who didn't have much access to the Museum.” Another stated, “I definitely see the need for continued investment in digital platforms to successfully engage culturally and geographically diverse audiences. Hybrid models are the future with live offerings supported by recorded or live-streamed components.”

A final positive comment from one respondent: “Our institution finally understands the value and necessity of digital engagement. Prior to the pandemic, the Museum operated as an ‘oasis’ and believed technology was a distraction in engaging with the artwork. We now have a fully dedicated distance learning studio and utilized various platforms to provide both synchronous and asynchronous engagement for school groups, lifelong learners, members, and our community…Digital engagement will only continue to grow due to low-cost, easily accessible platforms. Museums must embrace it or be left behind.”

Discussion

There is clearly disparity regarding the ease with which museums provide digital programming. Once museums were allowed to reopen, the momentum for virtual programming began to wane, especially for smaller to mid-sized museums. Staffing and funding had not adapted to keep virtual programming in place and efforts to monetize those programs did not reach sustainable levels. Museums counted on the flexibility of staff, often using their own equipment, to develop and post these new programs. Going back to work that had a pre-pandemic infrastructure often leaves the institutions without the digital grounding to keep virtual programming. Digital transformation efforts and the staff who made them possible were supported during the pandemic because there was no alternative for the museum to remain in the public eye. Institutional budgets are tight and whether small to mid-sized museums have the capacity to implement and maintain digital programming depends highly on the specific circumstances of the museum, its community, and its financial structure. First and foremost, the needs of the community that the museum serves should be met. This includes those inside of the museum working on the frontline, as well as those who access the programs offered. Partnerships and sponsorships with the community may prove the most valuable in keeping digital programming vibrant and cost effective.

Digital spaces provide small to mid-sized museums an opportunity to share all they have to offer on a larger scale since competition with larger institutions’ greater financial and staff resources is usually not possible. But if we’ve learned anything from this pandemic, it is that people are the most valuable resource of an institution. How we let staff innovate and reach out to communities will be what puts museums like Battleship New Jersey, which now has a YouTube channel with over one hundred thousand subscribers, on the map. The institution has about thirty full time staff (two thirds of which work on a large maintenance project that will end in a couple of years) and only saw around 80,000 guests a year pre-pandemic. Libby Jones, Director of Education & Digital Media at Battleship New Jersey, stated that the YouTube channel “was a massive increase in our ability to reach people. We have had school groups around the United States and abroad book virtual classes that saw our videos first and never would have known our museum existed without them.” After two years they now earn enough money from ads to pay the staff who make the videos with some left over to support the museum.

In terms of the future for their YouTube channel, “Sustainability is tough. We started making videos when the museum was closed and there weren’t any school groups or programs. Now we’re doing both. Managing both isn’t easy. We have to be strategic about the content we produce and the amount of time it takes to make it…We want to keep that engagement going and we’ve built a community around this, but we have to do it within the confines of our other responsibilities.” This underscores the wonderful capability and creativity of museum professionals as well as the constraints they face to make digital viable long-term in small to mid-sized institutions.

An important aspect of digital work is also acknowledging that a digital divide exists in terms of equity in access to the internet and technology. AAM published the article "How Can Education Programs Help Bridge the Digital Divide?" by Dr. Ebony Bailey and Dr. Kerry Sautner in which they state that in order to bridge this divide we must understand what our audiences need, create partnerships, and build longstanding and reciprocal relationships. These concepts are as important for any successful program outreach as they are for bridging the digital divide. They even apply to understanding the needs of frontline staff and educators to help make their invaluable work and the mission of the museum sustainable, whether it is in-person or digital.

When asked what the biggest disruptions for the next twelve months are, 76% of directors who responded to AAM’s December 2021to January 2022 National Snapshot of COVID-19 Impact on United States Museums survey stated the pandemic and future variants while 65% said a slow recovery for travel and tourism. Digital engagement has the potential to grow new audiences interested in what museums have to offer and spur tourism as more people begin to feel comfortable traveling again. As long as in-person programming is possible, there will always be a need and a desire for people to connect with each other and the physical museum. However, the digital world continues to expand and museums would be well served to use the lessons learned from the past two years to invest in digital infrastructure and, most importantly, their staff, in order to continue to extend the museum beyond the physical space.

Image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay.